Comics have been through a lot of crap. If comics were a person, they’d be that guy who looked like he had his life together, only to let it fall apart because of some gross secret addiction or a failed get-rich-quick scheme. Comics would hit rock bottom and show up to events wearing really inappropriate clothes and smelling a little weird, but Comics never would ask for help, but he’d just look at you with these eyes that still held a lingering spark of life. You forgot about Comics after you became sick of his drama… but years later, you’d run into him at the bookstore, and Comics would look pretty good again, and you’d strike up a friendship like you’d never spent any time apart. That cool guy that Comics used to be had returned, and it was awesome.

But you remain cautious.

1993 was an especially eventful year for comic books. At DC Comics, Superman had just died in a publisher-wide crossover, attracting a ton of media attention, and Batman is slowly going insane during Knightfall. Catwoman #1 with art by Jim Balent, showcases a Catwoman who wears a costume so tight that her bellybutton is visible. It’s basically nudity colored purple, and it’s a little embarrassing, but also emblematic of the era. DC launches Vertigo Comics, a separate line of comics which is geared towards “adult” readers, with a focus on the occult, graphic violence, and a purposeful eschewing of superheroes. Death, sex and magic all use 1993 to make a huge appearance.

On the other side of The Big Two, Marvel Comics publishes Maximum Carnage, a storyline which pits Spider-Man against a villain who is a mass of psychotic flesh and blood. They also launch a series of comics which place some of their main characters (Spider-Man, Hulk, Ghost Rider, the X-Men and Doctor Doom, among others) in the bleak, techno-punk landscape of the year 2099. Toy Biz chokes toy aisles with X-Men action figures depicting characters we’ve never heard of, don’t give a damn about, and will never hear of again. It’s all a desperate grab to carpetbomb nerds, hoping that something memorable and marketable will sift itself out. Ultimately, that thing was Deadpool, and even he accidentally fell out of the epitome of the worst of 1993: Rob Liefeld.

In 1993, a ton of small publishers pop up, flicker, and die within a few years. Image Comics thrives with Spawn and makes a significant dent in the two-publisher monopoly. Defiant Comics, on the other hand, epitomizes the hubris of 1993 comic publishing strategies, asking comic readers to purchase a large collection of trading cards and assemble them into a branded binder in order to read a single issue of Warriors of Plasm. Holographic, variant and foil covers place more importance on “collectible” comics than “readable” comics, and the whole thing collapses within a few years. But in 1993, there was a whole lot of hope. This is the scene.

In 1993, a ton of small publishers pop up, flicker, and die within a few years. Image Comics thrives with Spawn and makes a significant dent in the two-publisher monopoly. Defiant Comics, on the other hand, epitomizes the hubris of 1993 comic publishing strategies, asking comic readers to purchase a large collection of trading cards and assemble them into a branded binder in order to read a single issue of Warriors of Plasm. Holographic, variant and foil covers place more importance on “collectible” comics than “readable” comics, and the whole thing collapses within a few years. But in 1993, there was a whole lot of hope. This is the scene.

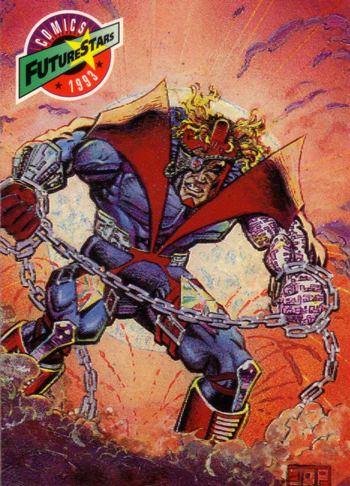

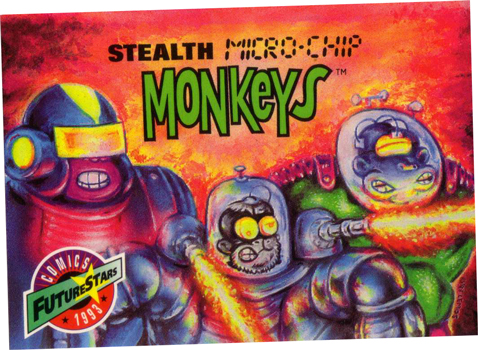

That idea of hope can be found captured in Majestic Entertainment’s Comics Futurestars : 1993 trading card line. Majestic, who have vanished without a trace as of this writing, originally popped up in 1993, published these cards and a few forgettable comics, and disappeared from human consciousness. These cards feature the creations of a bevy of new or emerging comic artists: some of these creators have gigs at Marvel or DC, and some have just stumbled out of a basement somewhere in Iowa. These artists were gathered from a wide variety of creative backgrounds, from courtroom sketch artists to hopeful kids to seasoned professionals. At this point in history, comics were trickling into a wider audience than the insular realm of nerd culture, and Comics Futurestars reflects on exactly how this influence was manifesting itself. Seeing people react to comics with their own creations is just as significant as what published comics were actually communicating.

Some of these cards ambitiously requested submissions to Majestic’s line of ‘1994 Comics Futurestars’ cards. Unfortunately, this series never happened. Had the line continued, it would have been an absorbing timeline of comic books, as reflected through the eyes of their biggest fans, as well as the steady improvement of comic art over the intervening decades.

If one were to make an anthropological assessment of comics in 1993 through this set of cards alone, the characters would break down into about ten categories, some of which may have some significant overlap.

It’s safe to say that most comics in 1993 had found a few main tropes to feed off of, and they fed upon those tropes until nothing was left but the bones. And then they used those bones in a comic, because 1993 was gritty, dammit. Bones everywhere. It’s not as though these tropes were all especially new; ‘The Urban Avenger’ dates back to Batman’s earliest appearance, and easily before then as well, but 1993 took special pleasure in making all of these things mysterious and edgy.

Each of these cards depicts a portrait of a previously-unknown character by a once-lesser-known artist. It’s not really explained in detail, but none of these characters really existed in any published works. Instead, these are things that lived in sketchbooks or in the back of brains until they had an outlet on a trading card. There’s a lot of wish fulfillment in that. The back of the card is a run-on sentence which merges each character’s bio with the creator’s bio, as well as a portrait. The portrait is often hilarious, as you’d expect from a bunch of late-20s-to-early-40s guys who took comics very, very seriously. Mullets, thin mustaches, sunglasses, and more than a few angry glares. Of course, the set includes a handful or women also, but in 1993 as it is today, comics is a testosterone-dominated trade.

The art ranges from extremely talented to a little less so, fully-painted to hastily-drawn, and completely original to painfully derivative. It was 1993. Everyone needed a lot of pouches for their cassette tapes and high ponytails so they could get into clubs. Twenty years later, these things are more apparent than ever. These cards are the equivalent of finding a high school yearbook and reading what everyone had written in the back, and not always knowing the references that were being made, or seeing how dated they are, still charming, and sometimes a little embarrassing.

What do these creators have to say about their creations, twenty years after their appearance? Are they now stars, in the future?

I contacted a collection of artists who participated in this project. Some were enthusiastic, some were confused that anyone remembered this set, and I was met with only one strange instance of vehement resistance – which, despite being disconcerting, was educational. As someone existing on the outside of the world of professional comics, one can only hear simplified reports about the concerns that exist within that world: creators’ rights, unauthorized re-purposing of work, and the bonds and squabbles between artists and/or their publishers. So, the idea that I might monetize these interviews by publishing them in a book (I won’t), or that I was asking for free work without offering compensation, was foreign to me, but these are real concerns for some comic creators today. An interview asks for an investment of time on the part of another party; sometimes, that party is compensated financially, but more often, the reward is promotion or a philosophical platform for the second party. Is that fair compensation? American Journalism Review states (and the Society of Professional Journalism Code of Ethics agrees):

“After all, it’s one of the Commandments of Good Journalism: Thou shalt not pay for information. Only the tabloids, of both the supermarket and TV variety, regard news as a tradable commodity.”

It’s a much larger discussion than can fit here, and I respect any artist who has declined direct participation, whatever their reason may be.

Some artists have unfortunately passed away, and some names have become almost universally recognizable: Dan Brereton, Brian Michael Bendis, and Paul Lee among them. Some predictions were accurate, and as expected, others were not – but every choice is indicative of an era. Here’s what they have to say about the last twenty years. Click through!

[This section will be added and amended as responses emerge from the depths of The Internet.]

C. David is a writer and artist living in the Hudson Valley, NY. He loves pinball, Wazmo Nariz, Rem Lezar, MODOK, pogs, Ultra Monsters, 80s horror, and is secretly very enthusiastic about everything else not listed here.

C. David is a writer and artist living in the Hudson Valley, NY. He loves pinball, Wazmo Nariz, Rem Lezar, MODOK, pogs, Ultra Monsters, 80s horror, and is secretly very enthusiastic about everything else not listed here.